Scripture: Luke 19:1-10 (the story of Jesus and Zaccheus)

What were the early Christians like? What kind of people were members of the early churches?

Some were like Zaccheus who, before he experienced Jesus as the Christ, was a chief tax collector and rich. In other words, he was a Jew who made his living by collaborating with Rome against his own people. And he was good at it -- so good at squeezing the money out of his own people that Rome made him chief tax collector, and so good at adding his own percentage on top of what he collected that he became rich.

No wonder when Jesus came through town and people lined the streets to see the teacher and healer, no one would let Zaccheus through to the front of the crowd. Zaccheus was little in stature, but that wasn't the only reason his own people looked down on him and pretended not to see him.

But then Zaccheus and Jesus meet. Jesus chooses to stay at Zaccheus's house. And Zaccheus in turn chooses to change his ways; he chooses to undo the wrongful gain that has been his livelihood.

So what kind of man is Zaccheus? What kind of life-story or narrative finds its way into the story of the early church?

Is Zaccheus just a miserable sinner who is embraced in ways he doesn't deserve, and who then makes restitution to the people he has wronged for the good of his soul and the easing of his conscience? No doubt this is part of what salvation is, and part of what our life-story and the story of church membership still is about today.

But is Zaccheus also a local hero? Is he someone who is employed in a wrong and unjust system, doing a job that hurts other people but pays him well (I'm just doing my job!), who when he comes to know Jesus, decides he can't do it anymore -- can't keep on ripping people off, can't continue to be part of something so wrong, can't stay inside a system so immoral. So he gives up his job and his comfortable place in the system, blows the whistle on the company (in this case, the Empire), and commits his life to something more whole and life-giving. Is this, too, part of what salvation is, and part of what our life-story and the story of church membership still must be about today?

Additional readings: Habbakuk 1:1-4 and 2:1-4; 2 Thessalonians 1:1-4, 11-12

Extra Helpings -- wanderings and wonderings in retirement ... staying in touch from a different place

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Towards Sunday, October 20, 2013

Series: Living missionally

Scripture: Jeremiah 31:27-34 and 2 Timothy 3:14-4:5

Where do we turn to know God and God's good will?

To the Bible (that we maybe know only a little about)? To preachers and teachers (both inside and outside the church, both helpful and unhelpful)? To our own heart (which has been shaped and informed by who knows what and how many influences)?

The prophet Jeremiah (around 580 BCE when the city of Jerusalem and the kingdom of Judah were in the process of being overthrown after centuries of superficially-faithful, mostly-unfaithful life) sees how ineffective it is for the people to put all their trust in only the written Scriptures, the handed-down traditions, and the way their leaders interpret them. He looks forward to a day promised by God when the knowledge of God and of God's good will for life will be written in every human heart, and people's own hearts will lead them to do God's good will for all life on Earth.

Centuries later, Timothy is a young man who started out knowing God and Christ in his heart from the teaching and example of his mother, his grandmother and a few godly elders. But now as a teacher and leader in the church himself, he is worn down by church politics, the influx of "other teaching" and casual immorality among the church members, and plain indifference on the part of church members to the kingdom of God. His heart is full of doubt and wavering, and he is not sure how to be of any help to himself or to others.

Where do we turn to know God and God's good will?

Do others need us at all (or do we need them) to know God and do God's good will for life on Earth?

Scripture: Jeremiah 31:27-34 and 2 Timothy 3:14-4:5

Where do we turn to know God and God's good will?

To the Bible (that we maybe know only a little about)? To preachers and teachers (both inside and outside the church, both helpful and unhelpful)? To our own heart (which has been shaped and informed by who knows what and how many influences)?

The prophet Jeremiah (around 580 BCE when the city of Jerusalem and the kingdom of Judah were in the process of being overthrown after centuries of superficially-faithful, mostly-unfaithful life) sees how ineffective it is for the people to put all their trust in only the written Scriptures, the handed-down traditions, and the way their leaders interpret them. He looks forward to a day promised by God when the knowledge of God and of God's good will for life will be written in every human heart, and people's own hearts will lead them to do God's good will for all life on Earth.

Centuries later, Timothy is a young man who started out knowing God and Christ in his heart from the teaching and example of his mother, his grandmother and a few godly elders. But now as a teacher and leader in the church himself, he is worn down by church politics, the influx of "other teaching" and casual immorality among the church members, and plain indifference on the part of church members to the kingdom of God. His heart is full of doubt and wavering, and he is not sure how to be of any help to himself or to others.

Where do we turn to know God and God's good will?

Do others need us at all (or do we need them) to know God and do God's good will for life on Earth?

Sermon from Sunday, October 13 (Thanksgiving Sunday)

Scripture: Genesis 2:4a-9, 15-17 and Isaiah 55:1-3, 6-13

Sermon: Thanksgiving plus ...

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival -- and more, and it’s the “and more” that I want to think about, because sometimes it’s the “and more” that we really need.

The history of Thanksgiving as we know it in Canada dates back to 1578 and the third voyage of the English explorer Martin Frobisher. Frobisher had been to the New World twice before searching for a Northwest Passage, and this time he was also to establish a small settlement. He set out with 15 ships, but along the way one -- the one with almost all the building materials for the settlement, was lost in a collision with ice. More ice and freak storms continued, scattering the rest of the fleet, and the crews feared for their survival. When they finally re-united at their anchorage in Frobisher Bay, the crews landed and Robert Wolfall, their minister and chaplain, preached what was called a godly sermon, exhorting the men to be thankful to God for their miraculous deliverance through dangerous places, and they shared in communion as a sign and seal of their death and resurrection in Christ.

A generation later the French attempted a settlement on Ste. Croix Island in the Bay of Fundy with almost 200 men landing on the island in 1604. The site was so poor and disease-susceptible that by spring of 1606, only 75 severely weakened men were left to carry on. Samuel de Champlain, one of the officers, moved the settlement across the Bay to Port Royale -- a more hospitable site, and some historians suggest that even then the settlement survived mostly because in November of that year Champlain created the Order of Good Cheer -- a weekly gathering through the winter months of all Order members and some of the local First Nations people to feast and to celebrate the gifts they were given, to give thanks for what they could do, and to encourage one another in counting and sharing their blessings.

Fifteen years later, it was the Pilgrims’ turn in Massachusetts. In 1620 when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock they were ill prepared for the New World. They struggled to survive the first winter with poor shelter, insufficient food, and no experience of New World agriculture and fishing. The next year the nearby Wampanoag tribe reached out to them -- taught them to fish for eel and to grow corn, and when the harvest that fall was bountiful, 53 Pilgrims and 90 members of the Wampanoag tribe shared a three-day harvest feast, with the Pilgrims expressing gratitude to God for their having been delivered from death and extinction.

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival -- and more. It’s an occasion of giving thanks to God for deliverance through dangerous places and survival against fearsome obstacles. It’s a practice that can be learned of celebrating what’s given, and encouraging one another in good cheer by counting and sharing blessings. It’s accepting and acknowledging much-needed help and support from others, and giving thanks for neighbours and strangers who help us survive a world we just weren’t prepared for.

And I wonder which of these it is for you this year, and for your family or household? I ask because we too live in, and through such times and landscapes.

All of us at times find ourselves on a journey through dark and dangerous places, with great obstacles and storms in our path that we fear we might not survive -- and we wonder, “Will we make it through?”

All of us at times end up in uncomfortable places that seem not good for our health or well-being, sometimes because of bad choices and poor planning, other times because life just happens -- and we wonder, “How ever did I get here? However did this happen to me?”

All of us at times also find ourselves in an unexpectedly strange new world we just don’t understand, that we seem to have nothing to offer to, and that makes all we know seem obsolete and irrelevant -- and we wonder, “Is this where I’m supposed to be? What good am I, or will I ever be in this place?”

We don’t have to be sailing with Frobisher, or settling with Champlain, or struggling with the Pilgrims to be facing these questions. We just need to be living in the world as it is. So I wonder: are any of these among the questions that you and yours face this year?

If so, Thanksgiving as a remembrance and celebration of hope in the power of God to see us through, is especially for you.

We’ve read from the prophet Isaiah:

Sermon: Thanksgiving plus ...

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival -- and more, and it’s the “and more” that I want to think about, because sometimes it’s the “and more” that we really need.

The history of Thanksgiving as we know it in Canada dates back to 1578 and the third voyage of the English explorer Martin Frobisher. Frobisher had been to the New World twice before searching for a Northwest Passage, and this time he was also to establish a small settlement. He set out with 15 ships, but along the way one -- the one with almost all the building materials for the settlement, was lost in a collision with ice. More ice and freak storms continued, scattering the rest of the fleet, and the crews feared for their survival. When they finally re-united at their anchorage in Frobisher Bay, the crews landed and Robert Wolfall, their minister and chaplain, preached what was called a godly sermon, exhorting the men to be thankful to God for their miraculous deliverance through dangerous places, and they shared in communion as a sign and seal of their death and resurrection in Christ.

A generation later the French attempted a settlement on Ste. Croix Island in the Bay of Fundy with almost 200 men landing on the island in 1604. The site was so poor and disease-susceptible that by spring of 1606, only 75 severely weakened men were left to carry on. Samuel de Champlain, one of the officers, moved the settlement across the Bay to Port Royale -- a more hospitable site, and some historians suggest that even then the settlement survived mostly because in November of that year Champlain created the Order of Good Cheer -- a weekly gathering through the winter months of all Order members and some of the local First Nations people to feast and to celebrate the gifts they were given, to give thanks for what they could do, and to encourage one another in counting and sharing their blessings.

Fifteen years later, it was the Pilgrims’ turn in Massachusetts. In 1620 when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock they were ill prepared for the New World. They struggled to survive the first winter with poor shelter, insufficient food, and no experience of New World agriculture and fishing. The next year the nearby Wampanoag tribe reached out to them -- taught them to fish for eel and to grow corn, and when the harvest that fall was bountiful, 53 Pilgrims and 90 members of the Wampanoag tribe shared a three-day harvest feast, with the Pilgrims expressing gratitude to God for their having been delivered from death and extinction.

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival -- and more. It’s an occasion of giving thanks to God for deliverance through dangerous places and survival against fearsome obstacles. It’s a practice that can be learned of celebrating what’s given, and encouraging one another in good cheer by counting and sharing blessings. It’s accepting and acknowledging much-needed help and support from others, and giving thanks for neighbours and strangers who help us survive a world we just weren’t prepared for.

And I wonder which of these it is for you this year, and for your family or household? I ask because we too live in, and through such times and landscapes.

All of us at times find ourselves on a journey through dark and dangerous places, with great obstacles and storms in our path that we fear we might not survive -- and we wonder, “Will we make it through?”

All of us at times end up in uncomfortable places that seem not good for our health or well-being, sometimes because of bad choices and poor planning, other times because life just happens -- and we wonder, “How ever did I get here? However did this happen to me?”

All of us at times also find ourselves in an unexpectedly strange new world we just don’t understand, that we seem to have nothing to offer to, and that makes all we know seem obsolete and irrelevant -- and we wonder, “Is this where I’m supposed to be? What good am I, or will I ever be in this place?”

We don’t have to be sailing with Frobisher, or settling with Champlain, or struggling with the Pilgrims to be facing these questions. We just need to be living in the world as it is. So I wonder: are any of these among the questions that you and yours face this year?

If so, Thanksgiving as a remembrance and celebration of hope in the power of God to see us through, is especially for you.

We’ve read from the prophet Isaiah:

Ho, everyone who thirsts, come

to the waters;

and you that have no money,

come, buy and eat!

Come, buy wine/milk without

money and without price.

Seek the Lord while he may be

found...

…and then you shall go out in

joy,

and be led back in peace;

…instead of the thorn shall come

up the cypress;

instead of the brier shall come

up the myrtle;

and it shall be to the Lord for

a memorial

for an everlasting sign of God’s

grace that

shall not end.

In

other words, we shall be fed -- as much as we need, by the grace of God. We shall find joy in place of sorrow, in

openness to God. And the place we are in

shall be fruitful and good, instead of empty, hurtful and fearful, by the working

of God in our time.

This

is a word of hope, and it is hope in the real world because the people Isaiah

speaks to are people who have suffered greatly, have had time to reflect on

their losses, and who have no illusions anymore about their own or other

people’s goodness, or about any guarantee of blessing or immunity from

suffering just because they are God’s people.

They know they have suffered in part because of their own sin and bad

choices, in part because of the ruthlessness and coldness of others, and in

part because sometimes bad stuff just happens.

They

are no longer children in some Garden of Eden.

They are adults with their eyes opened to the world as it is. And what Isaiah helps them see as part of

what the world is, is the real and present hope of God helping us endure and

survive what we face, and even thrive in spite of it -- maybe even because of it.

This is

the same Isaiah who also says,

Do

not fear, for I have redeemed you;

I

have called you by name, you are mine.

When

you pass through the waters,

I will be with you;

and

through the rivers,

they shall not

overwhelm you;

when

you walk through fire you shall not be burned,

and

the flame shall not consume you.

For

I am the Lord your God,

the Holy One, your

Saviour…

you

are precious in my sight, and I love you.

So what

is it you and your household face this year?

Are you sailing through dark and dangerous waters, with overwhelming

obstacles and problems that make you afraid?

Are you stuck in a bad spot -- no matter what the reason or who is to

blame, and not sure how things will change for the better? Are you somewhere you just don’t understand,

where you don’t how to cope or contribute, and where you might need to accept

the help of strangers -- even potential enemies or threats, to help you fit in?

Remember

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival -- and more.

It is a celebration of hope, a remembrance of God’s help in times past,

a promise that God will see you through to a new and joyous day.

As

Isaiah says to the people of his day in their time of fear and need:

For as the rain and the snow

come down from

heaven,

and do not return there

until they have

watered the earth,

making it bring forth and

sprout,

giving seed to the sower and

bread to the eater,

so shall my word be that goes

out from my mouth;

it shall not return to me empty,

but it shall accomplish that

which I purpose,

and succeed in the thing for

which I sent it.

Thanksgiving

is for you. As you remember and

celebrate God’s goodness, may it bring you joy, peace and hope, wherever you

are and however you remember and celebrate it.

Tuesday, October 08, 2013

Towards Thanksgiving Sunday (October 13, 2013)

Season: Creation

Scripture: Genesis 2:4b-9,15-17 and Isaiah 55:1-3, 6-13

Sermon: Cherishing the Gift (an adult Thanksgiving?)

Genesis 2 portrays our first home as a paradise, with all that is needed for good life freely given. We're tempted to think, "If only we had stayed there! It would be Thanksgiving every day!"

Scripture: Genesis 2:4b-9,15-17 and Isaiah 55:1-3, 6-13

Sermon: Cherishing the Gift (an adult Thanksgiving?)

Genesis 2 portrays our first home as a paradise, with all that is needed for good life freely given. We're tempted to think, "If only we had stayed there! It would be Thanksgiving every day!"

But is staying there ever in the cards? If we were meant to stay in the Garden, why in this story does God plant the tree of the knowledge of good and evil among the other trees, and then draw our attention so pointedly to it? How much more widely can God be opening the door to our fall from innocence, into knowledge, dis-illusionment (in the best sense) and awareness? And even giving us a little shove through it?

Isn't that fall precisely what's required for us to mature? As long as they are in the Garden and on the far side of fallen, Adam and Eve are like children and literally do not know enough truly to be thankful.

In contrast is the prophet of Isaiah 55 -- ecstatic in praise and thanksgiving to God. The prophet and people have suffered and endured great loss because of their sin and the ruthlessness of others. They have no illusions about their own goodness or the guarantee of blessings in life. So there is deep -- even ecstatic gratitude when they are able to envision again God's hand of blessing in their lives.

Have you noticed that all our cultural stories of "the first Thanksgiving" (whether Canadian or American) are about small groups of people who survive great ordeals by the grace of God? Thanksgiving comes on the far side of loss, anxiety and doubt, and we'll remember this in our celebration of Thanksgiving this year for the grace and goodness of God.

Sermon from Sunday, October 6, 2013

Scripture: Genesis 8:13-22

Sermon: Sustaining Life on Earth (what Noah knows)

Or is it maybe the only way?

Sacrifice is something we don’t always understand well. Often in stories like this we see it as a ritual act to satisfy the demands or appease the anger of a powerful god -- a pagan kind of thing in which if we give God this, God will let us keep that -- and if we don’t, God may feel slighted or injured and just take it all from us.

It really is a pagan kind of thing -- like a giant Mafia protection racket, with God as the godfather exacting a tribute and enforcing all our submissive loyalties. Or like the way we often talk about war, as the sacrifice of a few to the demands of the day for the survival of the many -- as though it’s a good thing, always necessary for the world’s well-being. Or the way we sometimes do economics, when the poor become collateral damage -- a necessary sacrifice suggested economists -- the priests of our time, for the well-being of the whole -- or at least for the comfort of the rest -- the propertied majority of a country or the privileged minority of the world.

This understanding and practice of sacrifice is quite pagan in the way it paints God as a jealous Mafia don, puts God and the gods of war in the same family, and puts God’s seal on systems that make the rich more important than the poor, and makes the poor disposable. And it’s right to wonder: is this any way make life on Earth sustainable?

Is this what Noah teaches us? Is this our spiritual DNA as heirs of Noah on the face of Earth?

I hope not … because there is a whole different meaning to sacrifice that is much more healthy and life-sustaining.

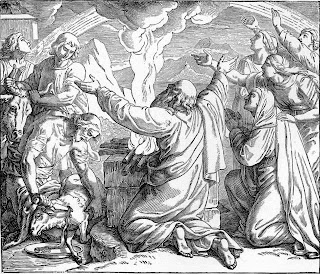

Do you notice that in the picture of Noah’s sacrifice there is no image of God? We see a rainbow … a sky mostly clear with just a few non-threatening clouds … and the smoke of the sacrificed animals rising up the heavens. But we see no image of God, and that’s entirely in keeping with Old Testament theology and practice … with the practice of the people of Israel not to make any images of God. Because who are they … and who are we, to think we can fathom the mysteries of the holy … comprehend the fullness of the divine … understand the real and final meaning of reality?

And that is what sacrifice is about in the best and most life-giving sense. It’s an act of remembering that we are not God and that what we have is not just our own -- that the Earth and all that is in it could just as easily not be, as be -- that ultimately nothing is ours to possess -- that whatever we have we hold in trust -- and we don’t even always know what’s best to do with it.

How tempting it must have been for Noah, his wife and their family, as they disembarked and set foot once again on Earth with all the surviving creatures, for them to think they were now in charge, that now it was up to them and only them to make this work right, that now they should take control and set down some rules and get themselves elected king and queen and royal family and hang on to this thing for all they worth and forever.

An exhilarating thought? An inspiring challenge? An exhausting burden? A proud illusion? Probably all of the above, and also at its heart a deep and universal temptation … that Noah at least at this moment of sacrifice is able to resist.

Because this sacrifice is Noah’s confession that he is not in control, that what he has done is not just of his own design, that what he has and what he has saved are not his to hang on to as possession or reward. In his sacrifice he says, this really is all gift. It’s originally made and ultimately held in the hand of a graciously loving God that I cannot even begin to comprehend. I let go of control to the greater design of this God -- whatever it is and will be, and I trust it.

Isn’t this how we live our lives at best? Isn’t this the way to run the world, and to sustain all life on Earth? To take our part in caring for what is and helping it survive, but always within the framework of not being in control, not making all that is our possession, letting ourselves be just one faithful part of the overall picture that’s painted by a creative and redeeming God greater than all?

Sometimes we choose this way. Parents do it with their children -- looking for and nurturing the good that is breathed into them by God, encouraging and seeking their growth, but without controlling, without imagining they know all that their kids should be or do, holding them lightly rather than tightly, and at a certain point -- maybe many points along the way, letting go and letting them be whatever they need to be.

Sometimes we do it with ourselves. This past Friday morning I woke up at 3 or 3:30 -- fully aware, with that disturbing clarity that comes at that time of the morning, while all is still dark, of a number of things I had done wrong over the few days before -- some mis-steps and bad choices here at work and at home -- none of them new, but all of them adding up to deep anxiety, regret and guilt, a sense of hopelessness.

In the dark of that moment I was tempted with two plans of action. One was to get up and start working -- just work all the harder at plans and schemes, take more control and work harder at what I hadn’t done right. The other was to turn over in bed and try to think about only good and pleasant things -- to escape into some kind of dream world and not have to face the mess I had made -- to make the world into something I could handle and be comfortable in.

After stewing for maybe ten or thirty minutes, I got up. Not to work, though. Not to just keep working harder at what I’d already worked too hard at. I got up to pray. I found a quiet place to sit, where I could look out a window at the darkened world beyond me, and I asked very simply for a sense of God’s presence with me and within me.

It began to come. The worries and anxieties also came up, of course. But as each came into my consciousness, I acknowledged it for what it was and then put into the sea, or maybe the stream of God’s presence that was flowing around and into me. Instead of hanging on to all the concerns and anxieties, all the mistakes I had made, I let them go … and as I did that, after half an hour or so, I began to see a bit of a way forward -- a good way, a new way, a few good next steps that could be taken -- not by my ingenious design, but by the creating and redeeming love of God.

There is a wisdom and a love and creative good will for all life that is greater than we are -- greater than any mistakes we make -- greater than any confusing twists and turns that we experience in life’s journey. And sometimes we choose to let go control and open ourselves to it.

Other times, life forces us to it.

In a way, this is what happened with the renovation of the Upper Room. It was 7 or 8 years ago -- maybe even 9 or 10, when we realized something had to be done to the room. It was a great room that had served the church well since it was built, but it was in disrepair and needed to be fixed up.

So we talked and made plans. We surveyed the congregation and came up with all our best thoughts. We raised funds and got grants. And after some stewing and wrestling, we started work on fixing our ark. We replaced the wiring, spent some time on the entrances, then got ready to insulate and repair and repaint the old high walls that were there. We had the project in hand. We were not always entirely happy, but we were committed to do what we needed to do.

And then the economic downturn happened. Money had to be redirected. Work came to a stop -- for a few long years. It was taken out of our hands. We had to sacrifice the project and let go of our plans -- as sad and morale-sapping as that was.

But in that break -- in that time -- that sabbath time maybe, of having things taken out of our hands, and of having to let go and wait, what happened? A new idea for the room came forward. A new vision for its design came to light -- from somewhere, through one or two people open to quiet and reflective thought, to a Council of people who know how to listen to wisdom beyond their own, there came a vision for the future of the room that in all our best busy-ness and commitment, we hadn’t imagined … but which immediately spoke to us all, which we now love, and for which we are very thankful.

When we let go control -- or it’s taken from us, there’s a chance of openness to a greater wisdom. When we hold what we have lightly rather than tightly, there’s a chance of its goodness and life being sustained. When we remember we are part -- but only part, of an incomprehensible mysterious good, we are free to share in it and share it more easily with others.

The sacrifice that needs to be made, and that Noah made the day he got off the ark, is the offering of what we have and who we are to the good will of the God who is always creating and redeeming the goodness of life that we are given as gift.

Sermon: Sustaining Life on Earth (what Noah knows)

After

all Noah went through to get to where he was, and to save what he had, you’d

think he’d be more anxious to hang on to it, and not let it go.

Of

course maybe after being locked into the ark for almost a year with all those

creatures, he was happy enough to be able to open the door, lower the gangplank

and let them go free -- see them leave his floating house, so he and his wife could

have a break. Empty nest? Oh, yeah!!!

You gotta love it!

But

to kill them! Even just some of

them. Within days -- maybe hours, of

setting foot again on almost solid, still-very-squooshy ground, Noah marks the

end of the Flood by sacrificing some of the better of the animals that have survived

the whole ordeal with him.

Or is it maybe the only way?

Sacrifice is something we don’t always understand well. Often in stories like this we see it as a ritual act to satisfy the demands or appease the anger of a powerful god -- a pagan kind of thing in which if we give God this, God will let us keep that -- and if we don’t, God may feel slighted or injured and just take it all from us.

It really is a pagan kind of thing -- like a giant Mafia protection racket, with God as the godfather exacting a tribute and enforcing all our submissive loyalties. Or like the way we often talk about war, as the sacrifice of a few to the demands of the day for the survival of the many -- as though it’s a good thing, always necessary for the world’s well-being. Or the way we sometimes do economics, when the poor become collateral damage -- a necessary sacrifice suggested economists -- the priests of our time, for the well-being of the whole -- or at least for the comfort of the rest -- the propertied majority of a country or the privileged minority of the world.

This understanding and practice of sacrifice is quite pagan in the way it paints God as a jealous Mafia don, puts God and the gods of war in the same family, and puts God’s seal on systems that make the rich more important than the poor, and makes the poor disposable. And it’s right to wonder: is this any way make life on Earth sustainable?

Is this what Noah teaches us? Is this our spiritual DNA as heirs of Noah on the face of Earth?

I hope not … because there is a whole different meaning to sacrifice that is much more healthy and life-sustaining.

Do you notice that in the picture of Noah’s sacrifice there is no image of God? We see a rainbow … a sky mostly clear with just a few non-threatening clouds … and the smoke of the sacrificed animals rising up the heavens. But we see no image of God, and that’s entirely in keeping with Old Testament theology and practice … with the practice of the people of Israel not to make any images of God. Because who are they … and who are we, to think we can fathom the mysteries of the holy … comprehend the fullness of the divine … understand the real and final meaning of reality?

And that is what sacrifice is about in the best and most life-giving sense. It’s an act of remembering that we are not God and that what we have is not just our own -- that the Earth and all that is in it could just as easily not be, as be -- that ultimately nothing is ours to possess -- that whatever we have we hold in trust -- and we don’t even always know what’s best to do with it.

How tempting it must have been for Noah, his wife and their family, as they disembarked and set foot once again on Earth with all the surviving creatures, for them to think they were now in charge, that now it was up to them and only them to make this work right, that now they should take control and set down some rules and get themselves elected king and queen and royal family and hang on to this thing for all they worth and forever.

An exhilarating thought? An inspiring challenge? An exhausting burden? A proud illusion? Probably all of the above, and also at its heart a deep and universal temptation … that Noah at least at this moment of sacrifice is able to resist.

Because this sacrifice is Noah’s confession that he is not in control, that what he has done is not just of his own design, that what he has and what he has saved are not his to hang on to as possession or reward. In his sacrifice he says, this really is all gift. It’s originally made and ultimately held in the hand of a graciously loving God that I cannot even begin to comprehend. I let go of control to the greater design of this God -- whatever it is and will be, and I trust it.

Isn’t this how we live our lives at best? Isn’t this the way to run the world, and to sustain all life on Earth? To take our part in caring for what is and helping it survive, but always within the framework of not being in control, not making all that is our possession, letting ourselves be just one faithful part of the overall picture that’s painted by a creative and redeeming God greater than all?

Sometimes we choose this way. Parents do it with their children -- looking for and nurturing the good that is breathed into them by God, encouraging and seeking their growth, but without controlling, without imagining they know all that their kids should be or do, holding them lightly rather than tightly, and at a certain point -- maybe many points along the way, letting go and letting them be whatever they need to be.

Sometimes we do it with ourselves. This past Friday morning I woke up at 3 or 3:30 -- fully aware, with that disturbing clarity that comes at that time of the morning, while all is still dark, of a number of things I had done wrong over the few days before -- some mis-steps and bad choices here at work and at home -- none of them new, but all of them adding up to deep anxiety, regret and guilt, a sense of hopelessness.

In the dark of that moment I was tempted with two plans of action. One was to get up and start working -- just work all the harder at plans and schemes, take more control and work harder at what I hadn’t done right. The other was to turn over in bed and try to think about only good and pleasant things -- to escape into some kind of dream world and not have to face the mess I had made -- to make the world into something I could handle and be comfortable in.

After stewing for maybe ten or thirty minutes, I got up. Not to work, though. Not to just keep working harder at what I’d already worked too hard at. I got up to pray. I found a quiet place to sit, where I could look out a window at the darkened world beyond me, and I asked very simply for a sense of God’s presence with me and within me.

It began to come. The worries and anxieties also came up, of course. But as each came into my consciousness, I acknowledged it for what it was and then put into the sea, or maybe the stream of God’s presence that was flowing around and into me. Instead of hanging on to all the concerns and anxieties, all the mistakes I had made, I let them go … and as I did that, after half an hour or so, I began to see a bit of a way forward -- a good way, a new way, a few good next steps that could be taken -- not by my ingenious design, but by the creating and redeeming love of God.

There is a wisdom and a love and creative good will for all life that is greater than we are -- greater than any mistakes we make -- greater than any confusing twists and turns that we experience in life’s journey. And sometimes we choose to let go control and open ourselves to it.

Other times, life forces us to it.

In a way, this is what happened with the renovation of the Upper Room. It was 7 or 8 years ago -- maybe even 9 or 10, when we realized something had to be done to the room. It was a great room that had served the church well since it was built, but it was in disrepair and needed to be fixed up.

So we talked and made plans. We surveyed the congregation and came up with all our best thoughts. We raised funds and got grants. And after some stewing and wrestling, we started work on fixing our ark. We replaced the wiring, spent some time on the entrances, then got ready to insulate and repair and repaint the old high walls that were there. We had the project in hand. We were not always entirely happy, but we were committed to do what we needed to do.

And then the economic downturn happened. Money had to be redirected. Work came to a stop -- for a few long years. It was taken out of our hands. We had to sacrifice the project and let go of our plans -- as sad and morale-sapping as that was.

But in that break -- in that time -- that sabbath time maybe, of having things taken out of our hands, and of having to let go and wait, what happened? A new idea for the room came forward. A new vision for its design came to light -- from somewhere, through one or two people open to quiet and reflective thought, to a Council of people who know how to listen to wisdom beyond their own, there came a vision for the future of the room that in all our best busy-ness and commitment, we hadn’t imagined … but which immediately spoke to us all, which we now love, and for which we are very thankful.

When we let go control -- or it’s taken from us, there’s a chance of openness to a greater wisdom. When we hold what we have lightly rather than tightly, there’s a chance of its goodness and life being sustained. When we remember we are part -- but only part, of an incomprehensible mysterious good, we are free to share in it and share it more easily with others.

The sacrifice that needs to be made, and that Noah made the day he got off the ark, is the offering of what we have and who we are to the good will of the God who is always creating and redeeming the goodness of life that we are given as gift.

Wednesday, October 02, 2013

A second step towards Sunday, October 6 (World Communion Sunday)

Alright ... time to get to work on being more sermon-ish. I delight in the ways Noah's character can be pictured, and yesterday I had my little fling. But now it's time to get practical.

After the Flood a first thing for Noah is to sacrifice some of the creatures that survived the Flood with him, as an offering to God. What does this have to do with us?

After the Flood a first thing for Noah is to sacrifice some of the creatures that survived the Flood with him, as an offering to God. What does this have to do with us?

Noah knows Earth can as easily not be, as be. The world is not "just there;" it is where it is by the love and good will of a creating, judging and redeeming God. To say Earth is, is not enough; it is sustained.

And there's the rub with our reality!

The need of sustainability is something we are rediscovering in everything we do -- whether global and national economics and development; the life of communities, families and churches; or even things like diet and exercise regimes.

Noah knows things are not just there; all things are held (or not) -- in love by God, in trust by us. And to say things are good is not enough; they are sustained (or not) in their goodness by God and by us as we make and act out particular kinds of choices.

As we look at Noah on his knees in the mud, choosing to sacrifice some part of what he has worked for, in recognition of a higher Power and greater good than his own, there must be something we learn about sustaining the goodness of what we have today.

Tuesday, October 01, 2013

Towards Sunday, October 6, 2013 (World Communion Sunday)

Season: Creation

Scripture: Genesis 8:20-22 and Psalm 104:1-9, 24-35

Sermon: Sustain Me!

OK ... imagine this scene.

The Flood is finally receded. For the first time in almost a year Noah, his family and all the creatures they saved from the waters are once again on not-yet-dry land.

They are exhausted by the ordeal. Elated it is finally over. Humbled and more than a little insecure at the inescapable realization of God's ability to destroy all, limited only by God's inexplicable desire not to destroy it altogether.

Noah, gripped by religious impulse, grabs some of the clean creatures that have survived and kills them with his own hands. He burns them on an altar. And as the smoke and smell of their burning flesh rises to the heavens, Noah falls to his knees in the mud and offers a prayer to God.

And the prayer he prays is ... Psalm 104. (Why not? I'm writing the play here, and it seems perfect.)

What a deep triangulated covenant of God, Earth and humanity is created, celebrated and cemented in that moment! God somewhere in the heavens -- creating, judging, yet also sustaining all that is. Earth in its muddy reality -- radiating for all time God's glory, but dependent in every moment on God's good will for its life. Humanity, God's conscious and self-conscious agents on Earth -- helping determine Earth's future, but always in the end on its knees sacrificially offering it back to God as God's own.

Does the scene seem pagan ... or holy? Does the covenant and what it requires seem primitive ... or universally true and faithful?

The British author Julian Barnes in his book, The History of the World in 9 1/2 Chapters, delightfully portrays the faithful, religious Noah as somewhat of a dangerous eccentric and insecure tyrant over the animals on board the ark. The fact that at the end he grabs and kills some of the best of them as a sacrifice to his God, mere moments after they have marked their survival of the ordeal of the Great Flood, only reinforces how irrational and arbitrary he and his notion of God must be.

Or is it maybe that the more we hang on to Earth and its creatures and make all we see, our own ... make the story just about Earth and us -- about what Earth means to us and what we can make of, and do with Earth ... squeeze God out of the picture ... stop kneeling in the mud and sacrificially giving it back to God ... put an end to the messy triangle, and more simply marry Earth just to our designs ...

... that we become the dangerously eccentric and irrational tyrants?

I'd love to wrote a play or short story about this. It could be delightful.

I have to write a sermon, though. It has to be helpful and honest to who and where and how we are.

What do you think the message is for us?

Scripture: Genesis 8:20-22 and Psalm 104:1-9, 24-35

Sermon: Sustain Me!

OK ... imagine this scene.

The Flood is finally receded. For the first time in almost a year Noah, his family and all the creatures they saved from the waters are once again on not-yet-dry land.

They are exhausted by the ordeal. Elated it is finally over. Humbled and more than a little insecure at the inescapable realization of God's ability to destroy all, limited only by God's inexplicable desire not to destroy it altogether.

Noah, gripped by religious impulse, grabs some of the clean creatures that have survived and kills them with his own hands. He burns them on an altar. And as the smoke and smell of their burning flesh rises to the heavens, Noah falls to his knees in the mud and offers a prayer to God.

And the prayer he prays is ... Psalm 104. (Why not? I'm writing the play here, and it seems perfect.)

What a deep triangulated covenant of God, Earth and humanity is created, celebrated and cemented in that moment! God somewhere in the heavens -- creating, judging, yet also sustaining all that is. Earth in its muddy reality -- radiating for all time God's glory, but dependent in every moment on God's good will for its life. Humanity, God's conscious and self-conscious agents on Earth -- helping determine Earth's future, but always in the end on its knees sacrificially offering it back to God as God's own.

Does the scene seem pagan ... or holy? Does the covenant and what it requires seem primitive ... or universally true and faithful?

The British author Julian Barnes in his book, The History of the World in 9 1/2 Chapters, delightfully portrays the faithful, religious Noah as somewhat of a dangerous eccentric and insecure tyrant over the animals on board the ark. The fact that at the end he grabs and kills some of the best of them as a sacrifice to his God, mere moments after they have marked their survival of the ordeal of the Great Flood, only reinforces how irrational and arbitrary he and his notion of God must be.

Or is it maybe that the more we hang on to Earth and its creatures and make all we see, our own ... make the story just about Earth and us -- about what Earth means to us and what we can make of, and do with Earth ... squeeze God out of the picture ... stop kneeling in the mud and sacrificially giving it back to God ... put an end to the messy triangle, and more simply marry Earth just to our designs ...

... that we become the dangerously eccentric and irrational tyrants?

I'd love to wrote a play or short story about this. It could be delightful.

I have to write a sermon, though. It has to be helpful and honest to who and where and how we are.

What do you think the message is for us?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)