Sermon: The reign of God in daily life is infectious; are we contagious?

It

doesn’t take much to make a difference and to help change the world. Maybe you’ve seen these ads.

It

doesn’t take much to change the world and help save it from its sin. Call it the butterfly effect. Dorothy Day uses the image of throwing our

pebble into the pond. Jesus talks about

sowing seed. Maybe we can call it the

infectiousness of good life, and the contagion of converted thinking.

However

we picture the joy of changing the world, we all have a place in it. We all have a part to play in the holy work

of turning the world from sin to more godly ways of being, and this is

something the Gospel story makes us think about.

In

Jesus’ time – as today, there is no shortage of religious teachers and leaders

and social and cultural authorities. In

the holy city, there are the priests – both high and low, who serve in the

Temple and in the royal court. There are

the scribes who study and know the old laws and writings. There are the Pharisees who know the Law of

Moses and all the different ways it has been interpreted over the

centuries. There are the Sadducees – the

religious side of the conservative upper crust, who usually see the Pharisees

as too liberal. There are the Essenes,

who live in community in the wild on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, for

the sake of a separate holiness. And in

every village there is the rabbi, or rabbis, and local elders that everyone

turns to for advice and direction.

There

is no shortage of religious teachers and authorities to do God’s work and

reveal God’s word for the time. But in

the Gospel when Jesus begins gathering followers to make a difference and help

save the world from its sin he turns to fishermen. He turns to common ordinary labourers, people

of the sea and of the street, people in the midst of everyday life with nothing

but willing hands and hearts and voices and spirits to offer – the basic things

God has given to us all.

This

point is emphasized in the old King James and un-corrected version we read

today, about “fishermen” being called to become “fishers of men.” Yes, there is good reason to change this

description of the first disciples by saying they are called from being

fishermen to start “fishing for people,” but the old unredeemed translation

makes the point even more clearly and poetically – that really it’s in the

midst of our daily life, whatever it is, that we’re called into Christian

discipleship through only a little change in how we see and describe ourselves

– a little change that makes all the difference in the world.

Parker

Palmer, for instance, has written a book called Courage to Teach in which he encourages and helps teachers to

understand themselves not just as transmitters and testers of information, but

as educators and nurturers of other human beings. In the same vein a caretaker in a school can

be just a worker doing a job and nothing more, or can be a model and a mentor

to others. Last year I met a Roman

Catholic priest who grew up without a father, and for whom the caretaker in the

one-room school he attended was the man who took him under his wing, gave him

and taught him responsibility around the school, and helped him believe in

himself. Anyone who’s been in a hospital

knows the difference between a doctor or nurse who really cares for the

patients in their care, and those who only care about and treat their symptoms. And the list could go on. If Jesus were to appear today and gather

disciples, it would be the ordinary and common people of the world he would go

to first – as he actually does.

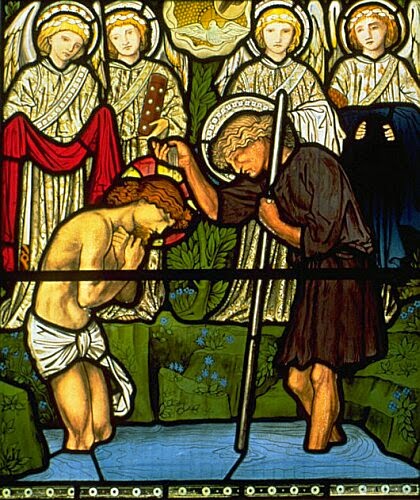

Discipleship

– following Jesus in such a way that we help to change the world, is something

we all are called into in our baptism, and are meant to be trained and equipped

for in our membership and participation in church. Maybe one thing to remember is that among the

first disciples of Jesus, it was only a few who left their daily lives for good

to become church leaders and missionaries and teachers. Most went back to their day jobs and homes

and families and friends and where they came from in the first place, and it’s

from there in the midst of the everyday stuff of life that they started to make

the difference that really changes the world and helps save it over and over

again from its sin.

The

kingdom of God – the reign of God in daily life, comes from the bottom up, not

top down. It comes from where we are and

in the midst of everyday life. It comes

as ordinary people agree to see themselves as servants of God and bearers of a

new way of life, as people who help spread the contagion of converted thinking

and living.

One

other thing that’s necessary, though, in addition to how we are willing to see

ourselves, is how we are willing to see other people. This is Jonah’s issue, and the fact that the

fable of Jonah has been saved by the people of Israel and included in their

Scriptures, shows that they understand it as an issue for all of us.

The

reason Jonah tries not to go to Nineveh – the capital city of Israel’s arch-enemy,

Assyria, and live out the word of God to the people there, is not that he fears

for his safety among them, that they will reject what he says and kill

him. Fear is not what he has to get

over.

What

he has to get over and have changed inside himself is his lack of concern for their

salvation. What he fears in the job God

gives him is that the people will listen, that they will actually repent of

their sin and wickedness, that God will then forgive them, and that instead of

being an enemy – an “other” against which Israel can comfortably define itself,

he and his people will have to embrace these others as fellow recipients of

God’s grace, equal to them as people of God’s love, fully part of what Israel

claims to be in the world. It’s easier –

more comfortable, for Jonah to see them as “them” than for the line between

“us” and “them” to be dissolved. I

wonder if maybe at some point he even would have been happier dying inside the

whale, than being spit out to go help convert and save the Ninevites.

And I

wonder what the question is for us in all this.

If good ways of living – God’s ways of saving the world from its sin and

making it good, are infectious, how contagious are we? And how happy or unconcerned are we to help

spread the infection to others – to the “them” around “us”?